Narrative of the 2006 Expedition

Having made substantial headway on the 2004 expedition to the Orenburg and Buzuluk area, we bid for additional funding. This time, we secured a substantial grant from the British Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) for a field and laboratory-based study of the Permo-Triassic transition in Russia. The key aims of the project are outlined on the .

The expedition was for one month, from mid-July to mid-August. The team was more or less the same as on the 2004 expedition, consisting of Tverdokhlebov and Surkov on the Russian side, and Benton, Newell, and Twitchett on the UK side. We added Graeme Taylor, a geomagnetics expert from the University of Plymouth because we had decided to carry out a detailed magnetostratigraphic survey of our key sections. We urgently required data from magnetostratigraphy to resolve a substantial dating dilemma that had emerged prior to the trip.

After the usual shenanigans of delayed flights, and unexpected lodging in Moscow for two nights, we travelled straight to Orenburg by train. The breakfast of dried fish and rive was delicious, but led to dire consequences for Richard Twitchett. We camped near Gavrilovka village first, as in 2004, and revisited classic sections with the Permo-Triassic boundary, at Sambullak, Tuyembetka, and Vodvizhenka, as well as the Early Triassic at Petropavlovka and the Late Permian at Kulchomovo.

Left: Restored cathedral and churches in the Saraktash monastery complex.

Left: Restored cathedral and churches in the Saraktash monastery complex.

On shopping days, we went into Saraktash, the nearest town, and looked around the markets and public buildings. The restored monastery of St Simeon (left) is a local marvel. It was closed down in Stalin’s day, when many of the monks were killed. Their memorials are in the monastery complex.

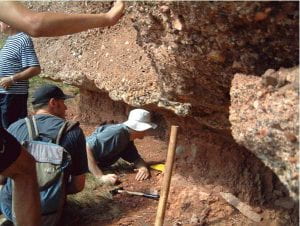

Sedimentary logging and magnetostratigraphic sampling at each location required endless digging. Generally, part of the section is visible, particularly the massive earliest Triassic sandstones and conglomerates, such as on Sambullak (above), but the softer sands, silts and muds between generally form low-angle slopes that are covered with rubble, soil, and grass. Two or three people worked continuously digging out trenches on the lower slopes at Sambullak, Tuyembetka, Vodvizhenka, Krasnogor, and other sites.

After three weeks in the Orenburg region, we drove back to Korolki, visited before on the 2004 Expedition, in order to complete and extend the earlier logging, but crucially to add magnetostratigraphic sampling. The Korolki Ravine provides one of the longest sections spanning the PTB: elsewhere, the sections are typically just through the Upper Permian, with a very little Triassic on top, or they often terminate just before the PTB.

We finish with evocative images of the heroic Uaz and Gaz as we begin to set up camp in the Korolki Ravine, and the mysterious scene of the Uaz parked in the middle of the wide and spacious steppe.