Narrative of the 2004 expedition

Palaeontologists from Bristol had visited Moscow in 1993, 1994, and 1995, and we had been part of a large field trip to the Orenburg region in the south Urals in 1995 (Benton 2003). After a break, the time was right for renewed work, and we obtained funding from the National Geographic Society to pay the costs of a 4-week expedition in July 2004. The Royal Society also provided funding for exchange visits between the two countries over a 2-year period.

The expedition was led by Valentin Tverdokhlebov, who had fifty years of experience mapping the Permo-Triassic red beds of the Orenburg area. Other Russian collaborators were Misha Surkov, our palaeontological collaborator and translator, as well as two of his students, Edvard Mamzurkin and Alexander (“Sasha”) Butyrin. The western team consisted of Mike Benton, professor of vertebrate palaeontology at the University of Bristol, Donald Benton, then 14, Richard Twitchett, then a postdoctoral researcher in Tokyo, and now at the University of Plymouth, Andy Newell, a former graduate student in Bristol and now a geologist with the British Geological Survey, and Cindy Looy, a Dutch palaeobotanist and palynologist who had worked with Twitchett on the PTB in Greenland.

After a flight to Moscow, and an overnight train journey to Saratov, the home base of the Russian team, we acquired the necessary stamps in our passports, and took the train from Saratov to Orenburg. Valentin Tverdokhlebov had already been there for a week or two and the camp was established on the banks of the River Sakmara, our old spot where we had spent most of the 1995 expedition (Photograph below). There was a cookhouse, with a full-sized domestic gas cooker run from large propane tanks, a cook, one dog, two drivers (one had also brought his 14-year-old son Dmitry). Comfortable, modern tents had been set up for us, equipped with camp beds. Valentin is a skilled camper and must have spent more than twenty years of his life under canvas: in the heyday of the Soviet Geological Survey, he spent three months in the field every summer, camping like this, in charge of twenty or more geologists and helpers, as he mapped vast swathes of the Soviet Union for his masters in Moscow.

We had three campsites: on the banks of the Sakmara for two weeks; then nearly one week in the Korolki Ravine beside the Elshanka River on the Asiatic side of the Ural River, near Sol-Iletsk; and, finally, on the banks of the Tok, near Buzuluk, halfway between Orenburg and Samara. Our purpose in visiting all these locations was to see as many good rock sections that spanned the PTB as we could, to produce sedimentary logs through these and to collect fossils and samples for isotopic study. While logging the Korolki Ravine we found the giant footprints nicknamed ‘big foot’.

These are some photographs taken on the 2004 Bristol-Saratov Permo-Triassic Boundary Expedition. Further accounts of the 2004 expedition may be found in Benton (2008) and an essay (in Russian) by Edward Mamzurkin and Alexander Butyrin, students who took part, at the Saratov State University website. We also have an illustrated narrative, kindly provided by Mick Oates.

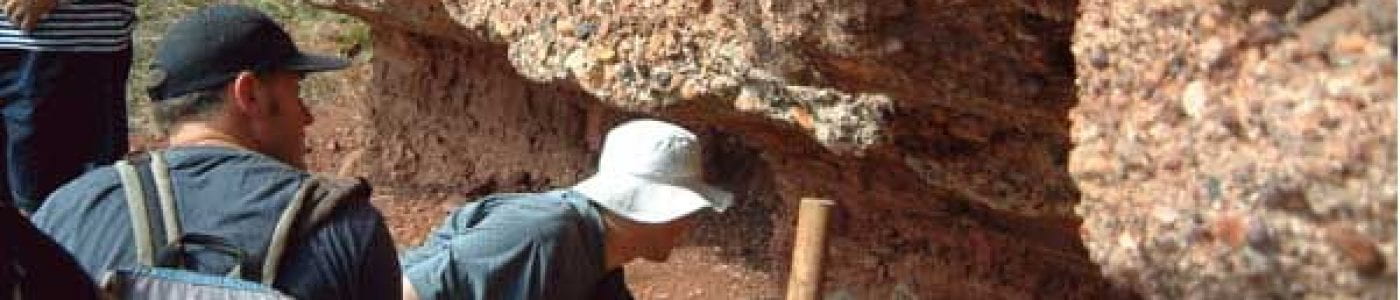

Water-laid sediments of the upper part of the Kulchomovskaya Svita (latest Permian) in the Korolki Ravine, near Sol-Iletsk, on the south-western margin of the Urals, Asiatic Russia. Members of the expedition engaged in making close observations. Close to this site, they found a number of huge footprints, nicknamed ‘bigfoot’ by our Russian colleagues. Water-laid sediments of the upper part of the Kulchomovskaya Svita (latest Permian) in the Korolki Ravine, near Sol-Iletsk, on the south-western margin of the Urals, Asiatic Russia. Members of the expedition engaged in making close observations. Close to this site, they found a number of huge footprints, nicknamed ‘bigfoot’ by our Russian colleagues. |

The Permo-Triassic boundary in Russia. The Kulchomovskaya Svita (latest Permian) below the ledge, and the Kopanskaya Svita (basalmost Triassic) above, in the Korolki Ravine, near Sol-Iletsk, on the south-western margin of the Urals, Asiatic Russia. The authors (left to right), Mikhail Surkov, Michael Benton and Valentin Tverdokhlebov inspect the sandstone lying right at the boundary.

The Permo-Triassic boundary in Russia. The rock formation at the top of Sambulla hill, near Saraktash, Orenburg region, European Russia, is a massive conglomerate deposited close to the western margin of the Ural Mountains at the very beginning of the Triassic. The grassy slope covers fine-grained latest Permian (Kulchomovskaya Svita) rocks, and the conglomerate marks the base of the Kopanskaya Svita (basalmost Triassic). Sedimentation returns to ‘normal’ above this conglomerate unit.

References

- Benton, M.J. 2015. When life nearly died: the greatest mass extinction of all time. Thames & Hudson, London.

- Benton, M. J. 2008. The end-Permian mass extinction – events on land in Russia. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 119, 119-136. pdf